Cori Talamantez knew who she was facing. Her McAllen Memorial Mustangs were battling star hitter Lexi Gonzalez and their biggest rival, the state’s third-ranked Class 6A team in McAllen High.

The Mustangs served the ball to Gonzalez, and Talamantez focused on what was happening next.

“I watched as she (Gonzalez) came in for a one,” Talamantez said, referring to a low, quick set meant to catch blockers out of place and create a 1-on-1 instead of a double block.

A junior libero, Talamantez barely had time to get her arms in the right spot when — “boom!” — the volleyball smashed into her readied arms from a signature thunderous attack by Gonzalez.

“Somehow I was in the right position and I popped it right up,” Talamantez said. “I got her that time.”

It wasn’t too long after that, however, when Gonzalez got her revenge, finding Talamantez cheating a little too far right. “She put it where I should have been,” the junior McAllen Memorial libero said. “She got me that time.”

But that’s what liberos do: they take on the biggest and baddest hitters on opposing teams. No matter how big or how bad, the best liberos will stand ready for any attack. They are a human target, the matador on the court being attacked at every possibility. The only difference — there is no ole’ — is liberos chase down the ball anywhere in the gym and are often seen diving across the floor time and again to save a ball and keep a rally alive.

Liberos are a fairly new position to the sport, but they are easy to pick out of a team, with each libero wearing a different color jersey than the rest of their teammates. Like the yellow jersey worn by the leader at the Tour de France, considered highly prestigious, the libero jersey signifies that this is the team’s best passer. The libero generally — but is not restricted to — replaces the middle blocker when that player goes to the back row. Since each team will have two middle blockers throughout each rotation, the libero is usually on the court for the entire game.

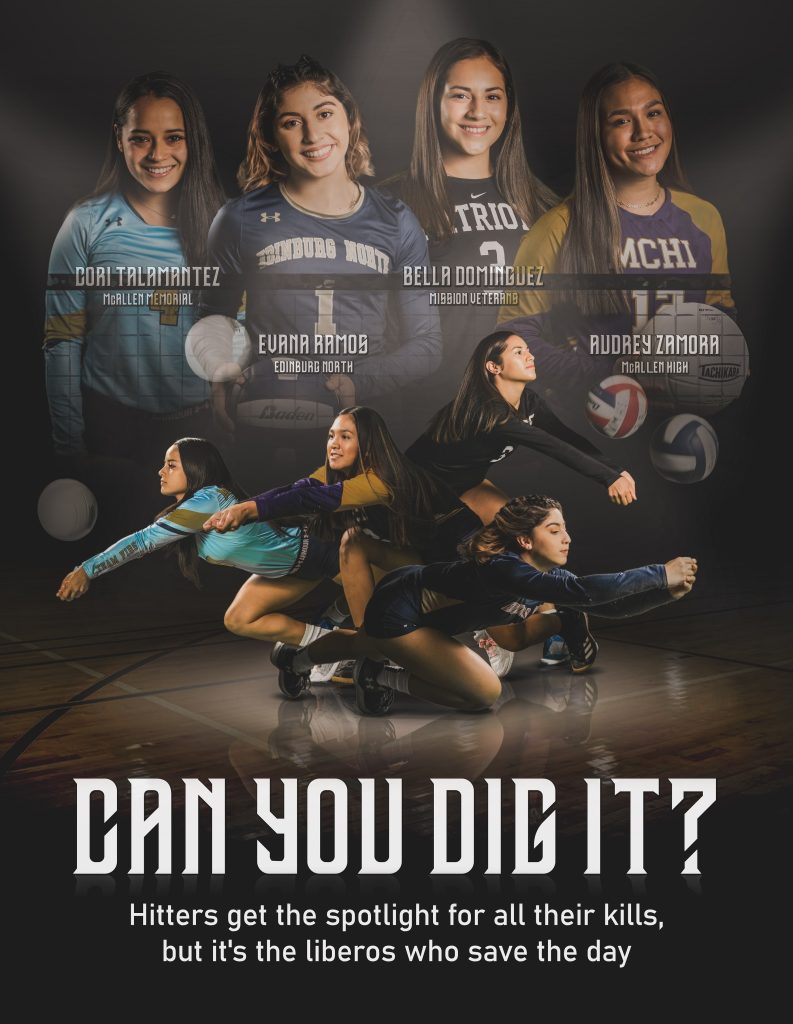

Liberos control the floor defensively, they are an extension of the defensive specialist, or better yet the defensive specialist is an extension of the libero. Such is especially the cases in Edinburg North’s Evana Ramos, McAllen High’s Audrey Zamora, McAllen Memorial’s Cori Talamantez and Mission Veterans’ Bella Dominguez. They have almost as much to do with the team’s kills as a setter or the hitter herself.

“Without a good pass, it’s a lot tougher for the hitters to get the ball on anything but a high outside set,” Mission Veterans head coach Diana Lerma said. “They are the ones we expect to get the ball to the target to set something up and keep the ball moving fast.”

The position was introduced in 1998 internationally but was used for the first time in 2002 by the NCAA. It reached the high school ranks in 2005.

“We were able to watch it at the collegiate level for a few years before it got to the high school level,” McAllen High head coach Paula Dodge said. “First, you have a person who specializes in defense who can be in there the entire time — that gives every team a huge benefit; somebody who is trained and focuses on defense and doesn’t count toward the number of substitutes. It allowed us as coach more freedom.”

Liberos, Lerma said, have changed the entire facet of the sport. It has brought more action to the court — and more interest from the fans.

“When you have a good libero, you can’t ever assume she’s not going to get to the ball, like with Bella,” Lerma said of her team’s libero. “Sometimes I wonder if she’s ever going to let the ball drop. A great libero is like that fly that will never go away.

“(Bella) is good with her feet and can make perfect passes with them, as well. That position upped the game to make it more competitive and to create more rallies for each and every point. It has become an exciting position to watch, but not so exciting when the other libero is doing it to you.”

Ramos, of Edinburg North, is one of the most statistically decorated leaders in the nation, according to MaxPreps.com. Ramos, as of Saturday, had accumulated a nation-best 1,000 digs in the 96 sets she has played so far. Dominguez was second in total digs at 872 digs in 106 sets. Ramos also was tops in digs per set, at 10.4 just ahead of Ashley Spencer of St. Francis Catholic in Gainesville, Florida.

“I love taking control in the back row,” Ramos said. “I love talking to my team, directing them where to go and letting them know that I’m behind them and have their backs.”

With action moving quickly, especially among the top teams, liberos have to read and react, anticipating where the attacker will be going with her kill attempt. While some may get jittery waiting on this to unfold, the best will slow everything down.

“My movement is very still and I calm down to see the hitter’s position and their hands,” Ramos said. “It’s about a lot of reading in the back row. I look at their hips to see if they are going to go cross (court) and I’ll read where their hand position and then move to where you think it’s going to be — read and move.”

Dominguez, the lone senior in the group, started out as a setter but said “I wasn’t really into setting.”

“I really wanted to be a libero,” she said. “I loving digging and saving balls and it’s what I wanted to do. I saw it as an opportunity to get more playing time and I really wanted to play.

Most of the girls described a bit of anxiety when they first took the floor in that position, with all of its responsibilities and knowing that would be attacked over and over throughout each match. Liberos, however, have a different mindset. They are like predators — they don’t back down and they’ll chase after their prey into the stands and out of the gym to keep the ball in play.

“It was a big transition from being a defensive specialist to a libero,” said Zamora, a junior who is starting at libero for the second year for McHi. “I knew I had to be louder and communicate more with people and tell there where to be and how to fix themselves.

“It was nerve-wracking. I didn’t want to let the team down and I wanted to prove that I deserved that jersey as a sophomore.”

“I’ve just continued to see her improved and one thing I’ve seen is that this is a girl who loves to pursue the ball and is always smiling because she loves playing volleyball and doing what she does,” Dodge said. “It doesn’t matter if it’s during a game or warmups. She works really hard and loves playing.”

For years, all the glory in a volleyball match would focus on the hitters with their massive strikes, now earning that libero jersey is a prize in itself, something that players all over the country work to earn.

“At first, it was someone else’s spot so I just kept working and would push myself at every practice and go all over the place,” Talamantez said. “I was talking and encouraging the team and suddenly one game Coach just said, ‘You’re the libero’ and it was against Mission Veterans with all their really hard hitters. ‘Gee, thanks Coach.’

“I was nervous but I knew that I had earned that jersey and I deserved it. Once I got that first hit, the jitters left.”

Hitters may still get all the attention due to the powerful kills they provide during a game, but the liberos have added more excitement to the sport but not letting those hitters have it so easy.

“They have made it even more exciting,” Dodge said. “The big kill has always brought the fans to their feet but now the level of play by defensive players when they make those big kills, it can make the entire gym come alive. They really are special players.”